ORC Specification v1

This version of the file format was originally released as part of Hive 0.12.

Motivation

Hive’s RCFile was the standard format for storing tabular data in Hadoop for several years. However, RCFile has limitations because it treats each column as a binary blob without semantics. In Hive 0.11 we added a new file format named Optimized Row Columnar (ORC) file that uses and retains the type information from the table definition. ORC uses type specific readers and writers that provide light weight compression techniques such as dictionary encoding, bit packing, delta encoding, and run length encoding – resulting in dramatically smaller files. Additionally, ORC can apply generic compression using zlib, or Snappy on top of the lightweight compression for even smaller files. However, storage savings are only part of the gain. ORC supports projection, which selects subsets of the columns for reading, so that queries reading only one column read only the required bytes. Furthermore, ORC files include light weight indexes that include the minimum and maximum values for each column in each set of 10,000 rows and the entire file. Using pushdown filters from Hive, the file reader can skip entire sets of rows that aren’t important for this query.

File Tail

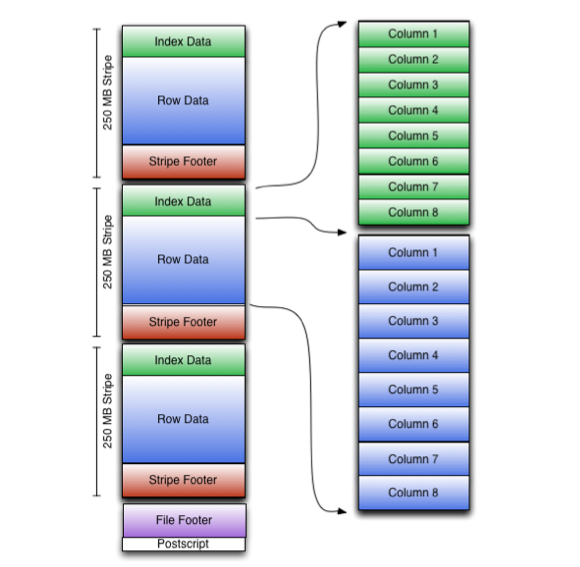

Since HDFS does not support changing the data in a file after it is written, ORC stores the top level index at the end of the file. The overall structure of the file is given in the figure above. The file’s tail consists of 3 parts; the file metadata, file footer and postscript.

The metadata for ORC is stored using Protocol Buffers, which provides the ability to add new fields without breaking readers. This document incorporates the Protobuf definition from the ORC source code and the reader is encouraged to review the Protobuf encoding if they need to understand the byte-level encoding

The sections of the file tail are (and their protobuf message type):

- encrypted stripe statistics: list of ColumnarStripeStatistics

- stripe statistics: Metadata

- footer: Footer

- postscript: PostScript

- psLen: byte

Postscript

The Postscript section provides the necessary information to interpret the rest of the file including the length of the file’s Footer and Metadata sections, the version of the file, and the kind of general compression used (eg. none, zlib, or snappy). The Postscript is never compressed and ends one byte before the end of the file. The version stored in the Postscript is the lowest version of Hive that is guaranteed to be able to read the file and it stored as a sequence of the major and minor version. This file version is encoded as [0,12].

The process of reading an ORC file works backwards through the file. Rather than making multiple short reads, the ORC reader reads the last 16k bytes of the file with the hope that it will contain both the Footer and Postscript sections. The final byte of the file contains the serialized length of the Postscript, which must be less than 256 bytes. Once the Postscript is parsed, the compressed serialized length of the Footer is known and it can be decompressed and parsed.

message PostScript {

// the length of the footer section in bytes

optional uint64 footerLength = 1;

// the kind of generic compression used

optional CompressionKind compression = 2;

// the maximum size of each compression chunk

optional uint64 compressionBlockSize = 3;

// the version of the writer

repeated uint32 version = 4 [packed = true];

// the length of the metadata section in bytes

optional uint64 metadataLength = 5;

// the fixed string "ORC"

optional string magic = 8000;

}

enum CompressionKind {

NONE = 0;

ZLIB = 1;

SNAPPY = 2;

LZO = 3;

LZ4 = 4;

ZSTD = 5;

}

Footer

The Footer section contains the layout of the body of the file, the type schema information, the number of rows, and the statistics about each of the columns.

The file is broken in to three parts- Header, Body, and Tail. The Header consists of the bytes “ORC’’ to support tools that want to scan the front of the file to determine the type of the file. The Body contains the rows and indexes, and the Tail gives the file level information as described in this section.

message Footer {

// the length of the file header in bytes (always 3)

optional uint64 headerLength = 1;

// the length of the file header and body in bytes

optional uint64 contentLength = 2;

// the information about the stripes

repeated StripeInformation stripes = 3;

// the schema information

repeated Type types = 4;

// the user metadata that was added

repeated UserMetadataItem metadata = 5;

// the total number of rows in the file

optional uint64 numberOfRows = 6;

// the statistics of each column across the file

repeated ColumnStatistics statistics = 7;

// the maximum number of rows in each index entry

optional uint32 rowIndexStride = 8;

// Each implementation that writes ORC files should register for a code

// 0 = ORC Java

// 1 = ORC C++

// 2 = Presto

// 3 = Scritchley Go from https://github.com/scritchley/orc

// 4 = Trino

// 5 = CUDF

optional uint32 writer = 9;

// information about the encryption in this file

optional Encryption encryption = 10;

// the number of bytes in the encrypted stripe statistics

optional uint64 stripeStatisticsLength = 11;

}

Stripe Information

The body of the file is divided into stripes. Each stripe is self contained and may be read using only its own bytes combined with the file’s Footer and Postscript. Each stripe contains only entire rows so that rows never straddle stripe boundaries. Stripes have three sections: a set of indexes for the rows within the stripe, the data itself, and a stripe footer. Both the indexes and the data sections are divided by columns so that only the data for the required columns needs to be read.

The encryptStripeId and encryptedLocalKeys support column encryption. They are set on the first stripe of each ORC file with column encryption and not set after that. For a stripe with the values set, the reader should use those values for that stripe. Subsequent stripes use the previous encryptStripeId + 1 and the same keys.

The current ORC merging code merges entire files, and thus the reader will get the correct values on what was the first stripe and continue on. If we develop a merge tool that reorders stripes or does partial merges, these values will need to be set correctly by that tool.

message StripeInformation {

// the start of the stripe within the file

optional uint64 offset = 1;

// the length of the indexes in bytes

optional uint64 indexLength = 2;

// the length of the data in bytes

optional uint64 dataLength = 3;

// the length of the footer in bytes

optional uint64 footerLength = 4;

// the number of rows in the stripe

optional uint64 numberOfRows = 5;

// If this is present, the reader should use this value for the encryption

// stripe id for setting the encryption IV. Otherwise, the reader should

// use one larger than the previous stripe's encryptStripeId.

// For unmerged ORC files, the first stripe will use 1 and the rest of the

// stripes won't have it set. For merged files, the stripe information

// will be copied from their original files and thus the first stripe of

// each of the input files will reset it to 1.

// Note that 1 was choosen, because protobuf v3 doesn't serialize

// primitive types that are the default (eg. 0).

optional uint64 encryptStripeId = 6;

// For each encryption variant, the new encrypted local key to use until we

// find a replacement.

repeated bytes encryptedLocalKeys = 7;

}

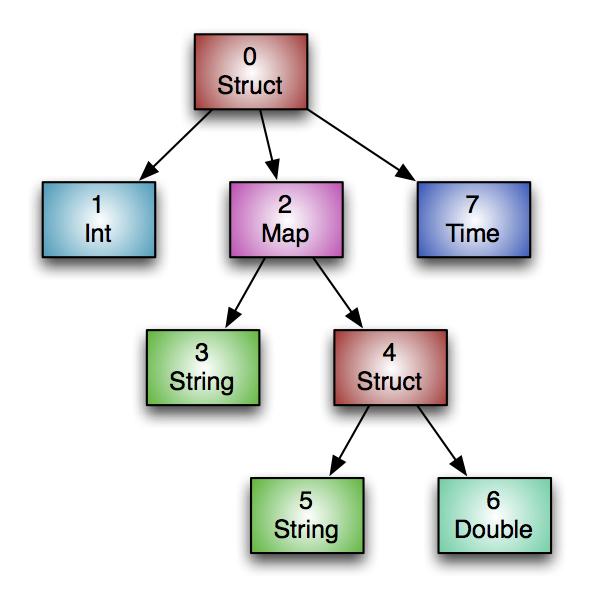

Type Information

All of the rows in an ORC file must have the same schema. Logically the schema is expressed as a tree as in the figure below, where the compound types have subcolumns under them.

The equivalent Hive DDL would be:

create table Foobar (

myInt int,

myMap map<string,

struct<myString : string,

myDouble: double>>,

myTime timestamp

);

The type tree is flattened in to a list via a pre-order traversal where each type is assigned the next id. Clearly the root of the type tree is always type id 0. Compound types have a field named subtypes that contains the list of their children’s type ids.

message Type {

enum Kind {

BOOLEAN = 0;

BYTE = 1;

SHORT = 2;

INT = 3;

LONG = 4;

FLOAT = 5;

DOUBLE = 6;

STRING = 7;

BINARY = 8;

TIMESTAMP = 9;

LIST = 10;

MAP = 11;

STRUCT = 12;

UNION = 13;

DECIMAL = 14;

DATE = 15;

VARCHAR = 16;

CHAR = 17;

TIMESTAMP_INSTANT = 18;

}

// the kind of this type

required Kind kind = 1;

// the type ids of any subcolumns for list, map, struct, or union

repeated uint32 subtypes = 2 [packed=true];

// the list of field names for struct

repeated string fieldNames = 3;

// the maximum length of the type for varchar or char in UTF-8 characters

optional uint32 maximumLength = 4;

// the precision and scale for decimal

optional uint32 precision = 5;

optional uint32 scale = 6;

}

Column Statistics

The goal of the column statistics is that for each column, the writer records the count and depending on the type other useful fields. For most of the primitive types, it records the minimum and maximum values; and for numeric types it additionally stores the sum. From Hive 1.1.0 onwards, the column statistics will also record if there are any null values within the row group by setting the hasNull flag. The hasNull flag is used by ORC’s predicate pushdown to better answer ‘IS NULL’ queries.

message ColumnStatistics {

// the number of values

optional uint64 numberOfValues = 1;

// At most one of these has a value for any column

optional IntegerStatistics intStatistics = 2;

optional DoubleStatistics doubleStatistics = 3;

optional StringStatistics stringStatistics = 4;

optional BucketStatistics bucketStatistics = 5;

optional DecimalStatistics decimalStatistics = 6;

optional DateStatistics dateStatistics = 7;

optional BinaryStatistics binaryStatistics = 8;

optional TimestampStatistics timestampStatistics = 9;

optional bool hasNull = 10;

}

For integer types (tinyint, smallint, int, bigint), the column statistics includes the minimum, maximum, and sum. If the sum overflows long at any point during the calculation, no sum is recorded.

message IntegerStatistics {

optional sint64 minimum = 1;

optional sint64 maximum = 2;

optional sint64 sum = 3;

}

For floating point types (float, double), the column statistics include the minimum, maximum, and sum. If the sum overflows a double, no sum is recorded.

message DoubleStatistics {

optional double minimum = 1;

optional double maximum = 2;

optional double sum = 3;

}

For strings, the minimum value, maximum value, and the sum of the lengths of the values are recorded.

message StringStatistics {

optional string minimum = 1;

optional string maximum = 2;

// sum will store the total length of all strings

optional sint64 sum = 3;

}

For booleans, the statistics include the count of false and true values.

message BucketStatistics {

repeated uint64 count = 1 [packed=true];

}

For decimals, the minimum, maximum, and sum are stored.

message DecimalStatistics {

optional string minimum = 1;

optional string maximum = 2;

optional string sum = 3;

}

Date columns record the minimum and maximum values as the number of days since the UNIX epoch (1/1/1970 in UTC).

message DateStatistics {

// min,max values saved as days since epoch

optional sint32 minimum = 1;

optional sint32 maximum = 2;

}

Timestamp columns record the minimum and maximum values as the number of

milliseconds since the UNIX epoch (1/1/1970 00:00:00). Before ORC-135, the

local timezone offset was included and they were stored as minimum and

maximum. After ORC-135, the timestamp is adjusted to UTC before being

converted to milliseconds and stored in minimumUtc and maximumUtc.

message TimestampStatistics {

// min,max values saved as milliseconds since epoch

optional sint64 minimum = 1;

optional sint64 maximum = 2;

// min,max values saved as milliseconds since UNIX epoch

optional sint64 minimumUtc = 3;

optional sint64 maximumUtc = 4;

}

Binary columns store the aggregate number of bytes across all of the values.

message BinaryStatistics {

// sum will store the total binary blob length

optional sint64 sum = 1;

}

User Metadata

The user can add arbitrary key/value pairs to an ORC file as it is written. The contents of the keys and values are completely application defined, but the key is a string and the value is binary. Care should be taken by applications to make sure that their keys are unique and in general should be prefixed with an organization code.

message UserMetadataItem {

// the user defined key

required string name = 1;

// the user defined binary value

required bytes value = 2;

}

File Metadata

The file Metadata section contains column statistics at the stripe level granularity. These statistics enable input split elimination based on the predicate push-down evaluated per a stripe.

message StripeStatistics {

repeated ColumnStatistics colStats = 1;

}

message Metadata {

repeated StripeStatistics stripeStats = 1;

}

Column Encryption

ORC as of Apache ORC 1.6 supports column encryption where the data and statistics of specific columns are encrypted on disk. Column encryption provides fine-grain column level security even when many users have access to the file itself. The encryption is transparent to the user and the writer only needs to define which columns and encryption keys to use. When reading an ORC file, if the user has access to the keys, they will get the real data. If they do not have the keys, they will get the masked data.

message Encryption {

// all of the masks used in this file

repeated DataMask mask = 1;

// all of the keys used in this file

repeated EncryptionKey key = 2;

// The encrypted variants.

// Readers should prefer the first variant that the user has access to

// the corresponding key. If they don't have access to any of the keys,

// they should get the unencrypted masked data.

repeated EncryptionVariant variants = 3;

// How are the local keys encrypted?

optional KeyProviderKind keyProvider = 4;

}

Each encrypted column in each file will have a random local key generated for it. Thus, even though all of the decryption happens locally in the reader, a malicious user that stores the key only enables access that column in that file. The local keys are encrypted by the Hadoop or Ranger Key Management Server (KMS). The encrypted local keys are stored in the file footer’s StripeInformation.

enum KeyProviderKind {

UNKNOWN = 0;

HADOOP = 1;

AWS = 2;

GCP = 3;

AZURE = 4;

}

When ORC is using the Hadoop or Ranger KMS, it generates a random encrypted local key (16 or 32 bytes for 128 or 256 bit AES respectively). Using the first 16 bytes as the IV, it uses AES/CTR to decrypt the local key.

With the AWS KMS, the GenerateDataKey method is used to create a new local key and the Decrypt method is used to decrypt it.

Data Masks

The user’s data is statically masked before writing the unencrypted variant. Because the masking was done statically when the file was written, the information about the masking is just informational.

The three standard masks are:

- nullify - all values become null

- redact - replace characters with constants such as X or 9

- sha256 - replace string with the SHA 256 of the value

The default is nullify, but masks may be defined by the user. Masks are not allowed to change the type of the column, just the values.

message DataMask {

// the kind of masking, which may include third party masks

optional string name = 1;

// parameters for the mask

repeated string maskParameters = 2;

// the unencrypted column roots this mask was applied to

repeated uint32 columns = 3 [packed = true];

}

Encryption Keys

In addition to the encrypted local keys, which are stored in the footer’s StripeInformation, the file also needs to describe the master key that was used to encrypt the local keys. The master keys are described by name, their version, and the encryption algorithm.

message EncryptionKey {

optional string keyName = 1;

optional uint32 keyVersion = 2;

optional EncryptionAlgorithm algorithm = 3;

}

The encryption algorithm is stored using an enumeration and since ProtoBuf uses the 0 value as a default, we added an unused value. That ensures that if we add a new algorithm that old readers will get UNKNOWN_ENCRYPTION instead of a real value.

enum EncryptionAlgorithm {

// used for detecting future algorithms

UNKNOWN_ENCRYPTION = 0;

// 128 bit AES/CTR

AES_CTR_128 = 1;

// 256 bit AES/CTR

AES_CTR_256 = 2;

}

Encryption Variants

Each encrypted column is written as two variants:

- encrypted unmasked - for users with access to the key

- unencrypted masked - for all other users

The changes to the format were done so that old ORC readers will read the masked unencrypted data. Encryption variants encrypt a subtree of columns and use a single local key. The initial version of encryption support only allows the two variants, but this may be extended later and thus readers should use the first variant of a column that the reader has access to.

message EncryptionVariant {

// the column id of the root column that is encrypted in this variant

optional uint32 root = 1;

// the key that encrypted this variant

optional uint32 key = 2;

// The master key that was used to encrypt the local key, referenced as

// an index into the Encryption.key list.

optional bytes encryptedKey = 3;

// the stripe statistics for this variant

repeated Stream stripeStatistics = 4;

// encrypted file statistics as a FileStatistics

optional bytes fileStatistics = 5;

}

Each variant stores stripe and file statistics separately. The file statistics are serialized as a FileStatistics, compressed, encrypted and stored in the EncryptionVariant.fileStatistics.

message FileStatistics {

repeated ColumnStatistics column = 1;

}

The stripe statistics for each column are serialized as ColumnarStripeStatistics, compressed, encrypted and stored in a stream of kind STRIPE_STATISTICS. By making the column stripe statistics independent of each other, the reader only reads and parses the columns contained in the SARG.

message ColumnarStripeStatistics {

// one value for each stripe in the file

repeated ColumnStatistics colStats = 1;

}

Stream Encryption

Our encryption is done using AES/CTR. CTR is a mode that has some very nice properties for us:

- It is seeded so that identical data is encrypted differently.

- It does not require padding the stream to the cipher length.

- It allows readers to seek in to a stream.

- The IV does not need to be randomly generated.

To ensure that we don’t reuse IV, we set the IV as:

- bytes 0 to 2 - column id

- bytes 3 to 4 - stream kind

- bytes 5 to 7 - stripe id

- bytes 8 to 15 - cipher block counter

However, it is critical for CTR that we never reuse an initialization vector (IV) with the same local key.

For data in the footer, use the number of stripes in the file as the stripe id. This guarantees when we write an intermediate footer in to a file that we don’t use the same IV.

Additionally, we never reuse a local key for new data. For example, when merging files, we don’t reuse local key from the input files for the new file tail, but always generate a new local key.

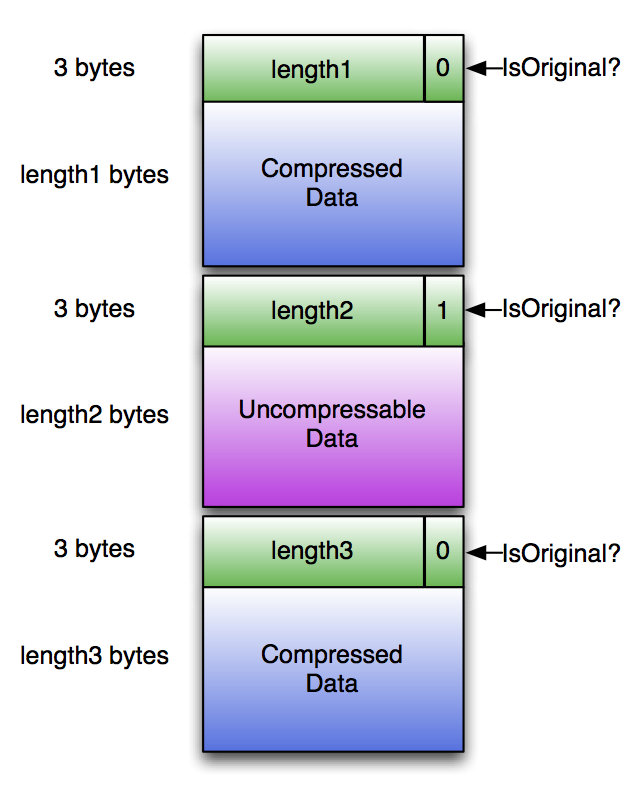

Compression

If the ORC file writer selects a generic compression codec (zlib or snappy), every part of the ORC file except for the Postscript is compressed with that codec. However, one of the requirements for ORC is that the reader be able to skip over compressed bytes without decompressing the entire stream. To manage this, ORC writes compressed streams in chunks with headers as in the figure below. To handle uncompressable data, if the compressed data is larger than the original, the original is stored and the isOriginal flag is set. Each header is 3 bytes long with (compressedLength * 2 + isOriginal) stored as a little endian value. For example, the header for a chunk that compressed to 100,000 bytes would be [0x40, 0x0d, 0x03]. The header for 5 bytes that did not compress would be [0x0b, 0x00, 0x00]. Each compression chunk is compressed independently so that as long as a decompressor starts at the top of a header, it can start decompressing without the previous bytes.

The default compression chunk size is 256K, but writers can choose their own value. Larger chunks lead to better compression, but require more memory. The chunk size is recorded in the Postscript so that readers can allocate appropriately sized buffers. Readers are guaranteed that no chunk will expand to more than the compression chunk size.

ORC files without generic compression write each stream directly with no headers.

Run Length Encoding

Base 128 Varint

Variable width integer encodings take advantage of the fact that most numbers are small and that having smaller encodings for small numbers shrinks the overall size of the data. ORC uses the varint format from Protocol Buffers, which writes data in little endian format using the low 7 bits of each byte. The high bit in each byte is set if the number continues into the next byte.

| Unsigned Original | Serialized |

|---|---|

| 0 | 0x00 |

| 1 | 0x01 |

| 127 | 0x7f |

| 128 | 0x80, 0x01 |

| 129 | 0x81, 0x01 |

| 16,383 | 0xff, 0x7f |

| 16,384 | 0x80, 0x80, 0x01 |

| 16,385 | 0x81, 0x80, 0x01 |

For signed integer types, the number is converted into an unsigned number using a zigzag encoding. Zigzag encoding moves the sign bit to the least significant bit using the expression (val « 1) ^ (val » 63) and derives its name from the fact that positive and negative numbers alternate once encoded. The unsigned number is then serialized as above.

| Signed Original | Unsigned |

|---|---|

| 0 | 0 |

| -1 | 1 |

| 1 | 2 |

| -2 | 3 |

| 2 | 4 |

Byte Run Length Encoding

For byte streams, ORC uses a very light weight encoding of identical values.

- Run - a sequence of at least 3 identical values

- Literals - a sequence of non-identical values

The first byte of each group of values is a header that determines whether it is a run (value between 0 to 127) or literal list (value between -128 to -1). For runs, the control byte is the length of the run minus the length of the minimal run (3) and the control byte for literal lists is the negative length of the list. For example, a hundred 0’s is encoded as [0x61, 0x00] and the sequence 0x44, 0x45 would be encoded as [0xfe, 0x44, 0x45]. The next group can choose either of the encodings.

Boolean Run Length Encoding

For encoding boolean types, the bits are put in the bytes from most significant to least significant. The bytes are encoded using byte run length encoding as described in the previous section. For example, the byte sequence [0xff, 0x80] would be one true followed by seven false values.

Integer Run Length Encoding, version 1

In Hive 0.11 ORC files used Run Length Encoding version 1 (RLEv1), which provides a lightweight compression of signed or unsigned integer sequences. RLEv1 has two sub-encodings:

- Run - a sequence of values that differ by a small fixed delta

- Literals - a sequence of varint encoded values

Runs start with an initial byte of 0x00 to 0x7f, which encodes the length of the run - 3. A second byte provides the fixed delta in the range of -128 to 127. Finally, the first value of the run is encoded as a base 128 varint.

For example, if the sequence is 100 instances of 7 the encoding would start with 100 - 3, followed by a delta of 0, and a varint of 7 for an encoding of [0x61, 0x00, 0x07]. To encode the sequence of numbers running from 100 to 1, the first byte is 100 - 3, the delta is -1, and the varint is 100 for an encoding of [0x61, 0xff, 0x64].

Literals start with an initial byte of 0x80 to 0xff, which corresponds to the negative of number of literals in the sequence. Following the header byte, the list of N varints is encoded. Thus, if there are no runs, the overhead is 1 byte for each 128 integers. Numbers [2, 3, 6, 7, 11] would be encoded as [0xfb, 0x02, 0x03, 0x06, 0x07, 0xb].

Integer Run Length Encoding, version 2

In Hive 0.12, ORC introduced Run Length Encoding version 2 (RLEv2), which has improved compression and fixed bit width encodings for faster expansion. RLEv2 uses four sub-encodings based on the data:

- Short Repeat - used for short sequences with repeated values

- Direct - used for random sequences with a fixed bit width

- Patched Base - used for random sequences with a variable bit width

- Delta - used for monotonically increasing or decreasing sequences

Short Repeat

The short repeat encoding is used for short repeating integer sequences with the goal of minimizing the overhead of the header. All of the bits listed in the header are from the first byte to the last and from most significant bit to least significant bit. If the type is signed, the value is zigzag encoded.

- 1 byte header

- 2 bits for encoding type (0)

- 3 bits for width (W) of repeating value (1 to 8 bytes)

- 3 bits for repeat count (3 to 10 values)

- W bytes in big endian format, which is zigzag encoded if they type is signed

The unsigned sequence of [10000, 10000, 10000, 10000, 10000] would be serialized with short repeat encoding (0), a width of 2 bytes (1), and repeat count of 5 (2) as [0x0a, 0x27, 0x10].

Direct

The direct encoding is used for integer sequences whose values have a relatively constant bit width. It encodes the values directly using a fixed width big endian encoding. The width of the values is encoded using the table below.

The 5 bit width encoding table for RLEv2:

| Width in Bits | Encoded Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | for delta encoding |

| 1 | 0 | for non-delta encoding |

| 2 | 1 | |

| 4 | 3 | |

| 8 | 7 | |

| 16 | 15 | |

| 24 | 23 | |

| 32 | 27 | |

| 40 | 28 | |

| 48 | 29 | |

| 56 | 30 | |

| 64 | 31 | |

| 3 | 2 | deprecated |

| 5 <= x <= 7 | x - 1 | deprecated |

| 9 <= x <= 15 | x - 1 | deprecated |

| 17 <= x <= 21 | x - 1 | deprecated |

| 26 | 24 | deprecated |

| 28 | 25 | deprecated |

| 30 | 26 | deprecated |

- 2 bytes header

- 2 bits for encoding type (1)

- 5 bits for encoded width (W) of values (1 to 64 bits) using the 5 bit width encoding table

- 9 bits for length (L) (1 to 512 values)

- W * L bits (padded to the next byte) encoded in big endian format, which is zigzag encoding if the type is signed

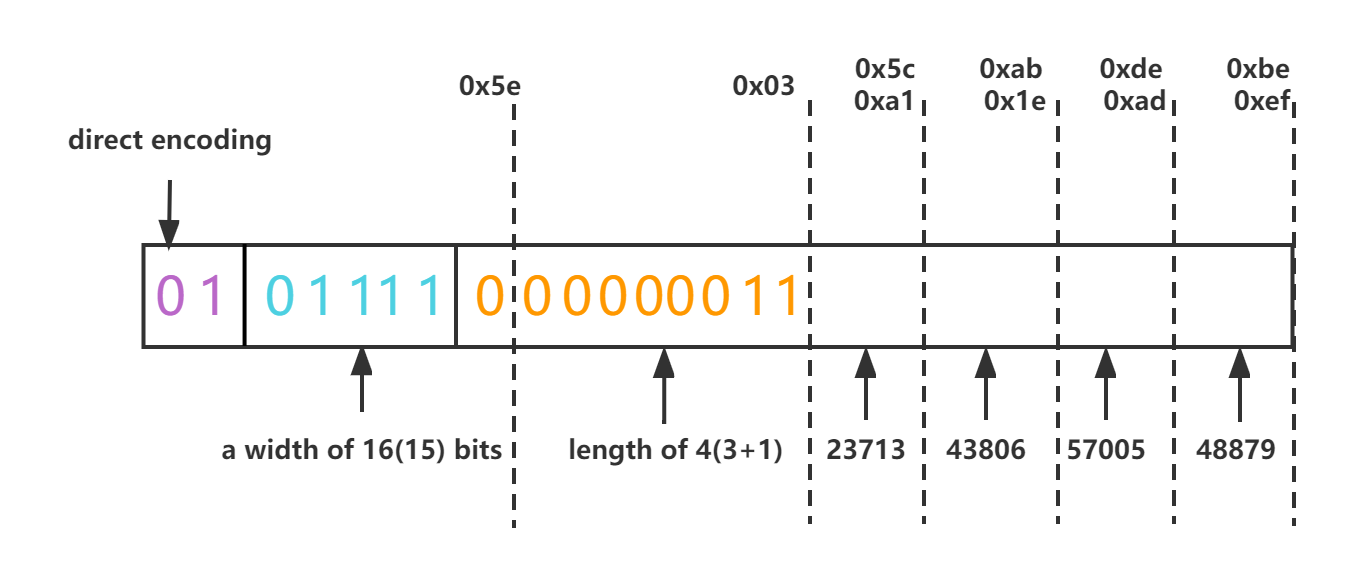

The unsigned sequence of [23713, 43806, 57005, 48879] would be serialized with direct encoding (1), a width of 16 bits (15), and length of 4 (3) as [0x5e, 0x03, 0x5c, 0xa1, 0xab, 0x1e, 0xde, 0xad, 0xbe, 0xef].

Note: the run length(4) is one-off. We can get 4 by adding 1 to 3 (See Hive-4123)

Patched Base

The patched base encoding is used for integer sequences whose bit widths varies a lot. The minimum signed value of the sequence is found and subtracted from the other values. The bit width of those adjusted values is analyzed and the 95 percentile of the bit width is chosen as W. The 5% of values larger than W use patches from a patch list to set the additional bits. Patches are encoded as a list of gaps in the index values and the additional value bits.

- 4 bytes header

- 2 bits for encoding type (2)

- 5 bits for encoded width (W) of values (1 to 64 bits) using the 5 bit width encoding table

- 9 bits for length (L) (1 to 512 values)

- 3 bits for base value width (BW) (1 to 8 bytes)

- 5 bits for patch width (PW) (1 to 64 bits) using the 5 bit width encoding table

- 3 bits for patch gap width (PGW) (1 to 8 bits)

- 5 bits for patch list length (PLL) (0 to 31 patches)

- Base value (BW bytes) - The base value is stored as a big endian value with negative values marked by the most significant bit set. If it that bit is set, the entire value is negated.

- Data values (W * L bits padded to the byte) - A sequence of W bit positive values that are added to the base value.

- Patch list (PLL * closestFixedBits(PGW + PW) bits) - A list of patches for values that didn’t fit within W bits. Each entry in the list consists of a gap, which is the number of elements skipped from the previous patch, and a patch value. Patches are applied by logically or’ing the data values with the relevant patch shifted W bits left. If a patch is 0, it was introduced to skip over more than 255 items. The combined length of each patch (PGW + PW) must be less or equal to 64. (PGW + PW) is padded to the closest fixed bit size according to the below table before being encoded in the patch list.

| (PGW + PW) | closestFixedBits(PGW + PW) |

|---|---|

| 1 <= x <= 24 | x |

| 25 | 26 |

| 26 | 26 |

| 27 | 28 |

| 28 | 28 |

| 29 | 30 |

| 30 | 30 |

| 31 | 32 |

| 32 | 32 |

| 33 <= x <= 40 | 40 |

| 41 <= x <= 48 | 48 |

| 49 <= x <= 56 | 56 |

| 57 <= x <= 64 | 64 |

The unsigned sequence of [2030, 2000, 2020, 1000000, 2040, 2050, 2060, 2070, 2080, 2090, 2100, 2110, 2120, 2130, 2140, 2150, 2160, 2170, 2180, 2190] has a minimum of 2000, which makes the adjusted sequence [30, 0, 20, 998000, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, 90, 100, 110, 120, 130, 140, 150, 160, 170, 180, 190]. It has an encoding of patched base (2), a bit width of 8 (7), a length of 20 (19), a base value width of 2 bytes (1), a patch width of 12 bits (11), patch gap width of 2 bits (1), and a patch list length of 1 (1). The base value is 2000 and the combined result is [0x8e, 0x13, 0x2b, 0x21, 0x07, 0xd0, 0x1e, 0x00, 0x14, 0x70, 0x28, 0x32, 0x3c, 0x46, 0x50, 0x5a, 0x64, 0x6e, 0x78, 0x82, 0x8c, 0x96, 0xa0, 0xaa, 0xb4, 0xbe, 0xfc, 0xe8]

Delta

The Delta encoding is used for monotonically increasing or decreasing sequences. The first two numbers in the sequence can not be identical, because the encoding is using the sign of the first delta to determine if the series is increasing or decreasing.

- 2 bytes header

- 2 bits for encoding type (3)

- 5 bits for encoded width (W) of deltas (0 to 64 bits) using the 5 bit width encoding table

- 9 bits for run length (L) (1 to 512 values)

- Base value - encoded as (signed or unsigned) varint

- Delta base - encoded as signed varint

- Delta values (W * (L - 2)) bytes - encode each delta after the first one. If the delta base is positive, the sequence is increasing and if it is negative the sequence is decreasing.

The unsigned sequence of [2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19, 23, 29] would be serialized with delta encoding (3), a width of 4 bits (3), length of 10 (9), a base of 2 (2), and first delta of 1 (2). The resulting sequence is [0xc6, 0x09, 0x02, 0x02, 0x22, 0x42, 0x42, 0x46].

Stripes

The body of ORC files consists of a series of stripes. Stripes are large (typically ~200MB) and independent of each other and are often processed by different tasks. The defining characteristic for columnar storage formats is that the data for each column is stored separately and that reading data out of the file should be proportional to the number of columns read.

In ORC files, each column is stored in several streams that are stored next to each other in the file. For example, an integer column is represented as two streams PRESENT, which uses one with a bit per value recording if the value is non-null, and DATA, which records the non-null values. If all of a column’s values in a stripe are non-null, the PRESENT stream is omitted from the stripe. For binary data, ORC uses three streams PRESENT, DATA, and LENGTH, which stores the length of each value. The details of each type will be presented in the following subsections.

The layout of each stripe looks like:

- index streams

- unencrypted

- encryption variant 1..N

- data streams

- unencrypted

- encryption variant 1..N

- stripe footer

There is a general order for index and data streams:

- Index streams are always placed together in the beginning of the stripe.

- Data streams are placed together after index streams (if any).

- Inside index streams or data streams, the unencrypted streams should be placed first and then followed by streams grouped by each encryption variant.

There is no fixed order within each unencrypted or encryption variant in the index and data streams:

- Different stream kinds of the same column can be placed in any order.

- Streams from different columns can even be placed in any order. To get the precise information (a.k.a stream kind, column id and location) of a stream within a stripe, the streams field in the StripeFooter described below is the single source of truth.

In the example of the integer column mentioned above, the order of the PRESENT stream and the DATA stream cannot be determined in advance. We need to get the precise information by StripeFooter.

Stripe Footer

The stripe footer contains the encoding of each column and the directory of the streams including their location.

message StripeFooter {

// the location of each stream

repeated Stream streams = 1;

// the encoding of each column

repeated ColumnEncoding columns = 2;

optional string writerTimezone = 3;

// one for each column encryption variant

repeated StripeEncryptionVariant encryption = 4;

}

If the file includes encrypted columns, those streams and column encodings are stored separately in a StripeEncryptionVariant per an encryption variant. Additionally, the StripeFooter will contain two additional virtual streams ENCRYPTED_INDEX and ENCRYPTED_DATA that allocate the space that is used by the encryption variants to store the encrypted index and data streams.

message StripeEncryptionVariant {

repeated Stream streams = 1;

repeated ColumnEncoding encoding = 2;

}

To describe each stream, ORC stores the kind of stream, the column id, and the stream’s size in bytes. The details of what is stored in each stream depends on the type and encoding of the column.

message Stream {

enum Kind {

// boolean stream of whether the next value is non-null

PRESENT = 0;

// the primary data stream

DATA = 1;

// the length of each value for variable length data

LENGTH = 2;

// the dictionary blob

DICTIONARY_DATA = 3;

// deprecated prior to Hive 0.11

// It was used to store the number of instances of each value in the

// dictionary

DICTIONARY_COUNT = 4;

// a secondary data stream

SECONDARY = 5;

// the index for seeking to particular row groups

ROW_INDEX = 6;

// original bloom filters used before ORC-101

BLOOM_FILTER = 7;

// bloom filters that consistently use utf8

BLOOM_FILTER_UTF8 = 8;

// Virtual stream kinds to allocate space for encrypted index and data.

ENCRYPTED_INDEX = 9;

ENCRYPTED_DATA = 10;

// stripe statistics streams

STRIPE_STATISTICS = 100;

// A virtual stream kind that is used for setting the encryption IV.

FILE_STATISTICS = 101;

}

required Kind kind = 1;

// the column id

optional uint32 column = 2;

// the number of bytes in the file

optional uint64 length = 3;

}

Depending on their type several options for encoding are possible. The encodings are divided into direct or dictionary-based categories and further refined as to whether they use RLE v1 or v2.

message ColumnEncoding {

enum Kind {

// the encoding is mapped directly to the stream using RLE v1

DIRECT = 0;

// the encoding uses a dictionary of unique values using RLE v1

DICTIONARY = 1;

// the encoding is direct using RLE v2

DIRECT_V2 = 2;

// the encoding is dictionary-based using RLE v2

DICTIONARY_V2 = 3;

}

required Kind kind = 1;

// for dictionary encodings, record the size of the dictionary

optional uint32 dictionarySize = 2;

}

Column Encodings

SmallInt, Int, and BigInt Columns

All of the 16, 32, and 64 bit integer column types use the same set of potential encodings, which is basically whether they use RLE v1 or v2. If the PRESENT stream is not included, all of the values are present. For values that have false bits in the present stream, no values are included in the data stream.

| Encoding | Stream Kind | Optional | Contents |

|---|---|---|---|

| DIRECT | PRESENT | Yes | Boolean RLE |

| DATA | No | Signed Integer RLE v1 | |

| DIRECT_V2 | PRESENT | Yes | Boolean RLE |

| DATA | No | Signed Integer RLE v2 |

Note that the order of the Stream is not fixed. It also applies to other Column types.

Float and Double Columns

Floating point types are stored using IEEE 754 floating point bit layout. Float columns use 4 bytes per value and double columns use 8 bytes.

| Encoding | Stream Kind | Optional | Contents |

|---|---|---|---|

| DIRECT | PRESENT | Yes | Boolean RLE |

| DATA | No | IEEE 754 floating point representation |

String, Char, and VarChar Columns

String, char, and varchar columns may be encoded either using a dictionary encoding or a direct encoding. A direct encoding should be preferred when there are many distinct values. In all of the encodings, the PRESENT stream encodes whether the value is null. The Java ORC writer automatically picks the encoding after the first row group (10,000 rows).

For direct encoding the UTF-8 bytes are saved in the DATA stream and the length of each value is written into the LENGTH stream. In direct encoding, if the values were [“Nevada”, “California”]; the DATA would be “NevadaCalifornia” and the LENGTH would be [6, 10].

For dictionary encodings the dictionary is sorted (in lexicographical order of bytes in the UTF-8 encodings) and UTF-8 bytes of each unique value are placed into DICTIONARY_DATA. The length of each item in the dictionary is put into the LENGTH stream. The DATA stream consists of the sequence of references to the dictionary elements.

In dictionary encoding, if the values were [“Nevada”, “California”, “Nevada”, “California”, and “Florida”]; the DICTIONARY_DATA would be “CaliforniaFloridaNevada” and LENGTH would be [10, 7, 6]. The DATA would be [2, 0, 2, 0, 1].

| Encoding | Stream Kind | Optional | Contents |

|---|---|---|---|

| DIRECT | PRESENT | Yes | Boolean RLE |

| DATA | No | String contents | |

| LENGTH | No | Unsigned Integer RLE v1 | |

| DICTIONARY | PRESENT | Yes | Boolean RLE |

| DATA | No | Unsigned Integer RLE v1 | |

| DICTIONARY_DATA | No | String contents | |

| LENGTH | No | Unsigned Integer RLE v1 | |

| DIRECT_V2 | PRESENT | Yes | Boolean RLE |

| DATA | No | String contents | |

| LENGTH | No | Unsigned Integer RLE v2 | |

| DICTIONARY_V2 | PRESENT | Yes | Boolean RLE |

| DATA | No | Unsigned Integer RLE v2 | |

| DICTIONARY_DATA | No | String contents | |

| LENGTH | No | Unsigned Integer RLE v2 |

Boolean Columns

Boolean columns are rare, but have a simple encoding.

| Encoding | Stream Kind | Optional | Contents |

|---|---|---|---|

| DIRECT | PRESENT | Yes | Boolean RLE |

| DATA | No | Boolean RLE |

TinyInt Columns

TinyInt (byte) columns use byte run length encoding.

| Encoding | Stream Kind | Optional | Contents |

|---|---|---|---|

| DIRECT | PRESENT | Yes | Boolean RLE |

| DATA | No | Byte RLE |

Binary Columns

Binary data is encoded with a PRESENT stream, a DATA stream that records the contents, and a LENGTH stream that records the number of bytes per a value.

| Encoding | Stream Kind | Optional | Contents |

|---|---|---|---|

| DIRECT | PRESENT | Yes | Boolean RLE |

| DATA | No | String contents | |

| LENGTH | No | Unsigned Integer RLE v1 | |

| DIRECT_V2 | PRESENT | Yes | Boolean RLE |

| DATA | No | String contents | |

| LENGTH | No | Unsigned Integer RLE v2 |

Decimal Columns

Decimal was introduced in Hive 0.11 with infinite precision (the total number of digits). In Hive 0.13, the definition was change to limit the precision to a maximum of 38 digits, which conveniently uses 127 bits plus a sign bit. The current encoding of decimal columns stores the integer representation of the value as an unbounded length zigzag encoded base 128 varint. The scale is stored in the SECONDARY stream as a signed integer.

| Encoding | Stream Kind | Optional | Contents |

|---|---|---|---|

| DIRECT | PRESENT | Yes | Boolean RLE |

| DATA | No | Unbounded base 128 varints | |

| SECONDARY | No | Signed Integer RLE v1 | |

| DIRECT_V2 | PRESENT | Yes | Boolean RLE |

| DATA | No | Unbounded base 128 varints | |

| SECONDARY | No | Signed Integer RLE v2 |

Date Columns

Date data is encoded with a PRESENT stream, a DATA stream that records the number of days after January 1, 1970 in UTC.

| Encoding | Stream Kind | Optional | Contents |

|---|---|---|---|

| DIRECT | PRESENT | Yes | Boolean RLE |

| DATA | No | Signed Integer RLE v1 | |

| DIRECT_V2 | PRESENT | Yes | Boolean RLE |

| DATA | No | Signed Integer RLE v2 |

Timestamp Columns

Timestamp records times down to nanoseconds as a PRESENT stream that records non-null values, a DATA stream that records the number of seconds after 1 January 2015, and a SECONDARY stream that records the number of nanoseconds.

Because the number of nanoseconds often has a large number of trailing zeros, the number has trailing decimal zero digits removed and the last three bits are used to record how many zeros were removed. if the trailing zeros are more than 2. Thus 1000 nanoseconds would be serialized as 0x0a and 100000 would be serialized as 0x0c.

| Encoding | Stream Kind | Optional | Contents |

|---|---|---|---|

| DIRECT | PRESENT | Yes | Boolean RLE |

| DATA | No | Signed Integer RLE v1 | |

| SECONDARY | No | Unsigned Integer RLE v1 | |

| DIRECT_V2 | PRESENT | Yes | Boolean RLE |

| DATA | No | Signed Integer RLE v2 | |

| SECONDARY | No | Unsigned Integer RLE v2 |

Struct Columns

Structs have no data themselves and delegate everything to their child columns except for their PRESENT stream. They have a child column for each of the fields.

| Encoding | Stream Kind | Optional | Contents |

|---|---|---|---|

| DIRECT | PRESENT | Yes | Boolean RLE |

List Columns

Lists are encoded as the PRESENT stream and a length stream with number of items in each list. They have a single child column for the element values.

| Encoding | Stream Kind | Optional | Contents |

|---|---|---|---|

| DIRECT | PRESENT | Yes | Boolean RLE |

| LENGTH | No | Unsigned Integer RLE v1 | |

| DIRECT_V2 | PRESENT | Yes | Boolean RLE |

| LENGTH | No | Unsigned Integer RLE v2 |

Map Columns

Maps are encoded as the PRESENT stream and a length stream with number of items in each map. They have a child column for the key and another child column for the value.

| Encoding | Stream Kind | Optional | Contents |

|---|---|---|---|

| DIRECT | PRESENT | Yes | Boolean RLE |

| LENGTH | No | Unsigned Integer RLE v1 | |

| DIRECT_V2 | PRESENT | Yes | Boolean RLE |

| LENGTH | No | Unsigned Integer RLE v2 |

Union Columns

Unions are encoded as the PRESENT stream and a tag stream that controls which potential variant is used. They have a child column for each variant of the union. Currently ORC union types are limited to 256 variants, which matches the Hive type model.

| Encoding | Stream Kind | Optional | Contents |

|---|---|---|---|

| DIRECT | PRESENT | Yes | Boolean RLE |

| DATA | No | Byte RLE |

Indexes

Row Group Index

The row group indexes consist of a ROW_INDEX stream for each primitive column that has an entry for each row group. Row groups are controlled by the writer and default to 10,000 rows. Each RowIndexEntry gives the position of each stream for the column and the statistics for that row group.

The index streams are placed at the front of the stripe, because in the default case of streaming they do not need to be read. They are only loaded when either predicate push down is being used or the reader seeks to a particular row.

message RowIndexEntry {

repeated uint64 positions = 1 [packed=true];

optional ColumnStatistics statistics = 2;

}

message RowIndex {

repeated RowIndexEntry entry = 1;

}

To record positions, each stream needs a sequence of numbers. For uncompressed streams, the position is the byte offset of the RLE run’s start location followed by the number of values that need to be consumed from the run. In compressed streams, the first number is the start of the compression chunk in the stream, followed by the number of decompressed bytes that need to be consumed, and finally the number of values consumed in the RLE.

For columns with multiple streams, the sequences of positions in each stream are concatenated. That was an unfortunate decision on my part that we should fix at some point, because it makes code that uses the indexes error-prone.

Because dictionaries are accessed randomly, there is not a position to record for the dictionary and the entire dictionary must be read even if only part of a stripe is being read.

Note that for columns with multiple streams, the order of stream positions in the RowIndex is fixed, which may be different to the actual data stream placement, and it is the same as Column Encodings section we described above.

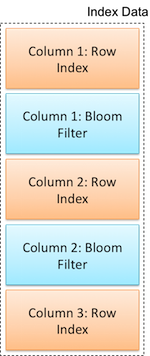

Bloom Filter Index

Bloom Filters are added to ORC indexes from Hive 1.2.0 onwards. Predicate pushdown can make use of bloom filters to better prune the row groups that do not satisfy the filter condition. The bloom filter indexes consist of a BLOOM_FILTER stream for each column specified through ‘orc.bloom.filter.columns’ table properties. A BLOOM_FILTER stream records a bloom filter entry for each row group (default to 10,000 rows) in a column. Only the row groups that satisfy min/max row index evaluation will be evaluated against the bloom filter index.

Each bloom filter entry stores the number of hash functions (‘k’) used and the bitset backing the bloom filter. The original encoding (pre ORC-101) of bloom filters used the bitset field encoded as a repeating sequence of longs in the bitset field with a little endian encoding (0x1 is bit 0 and 0x2 is bit 1.) After ORC-101, the encoding is a sequence of bytes with a little endian encoding in the utf8bitset field.

message BloomFilter {

optional uint32 numHashFunctions = 1;

repeated fixed64 bitset = 2;

optional bytes utf8bitset = 3;

}

message BloomFilterIndex {

repeated BloomFilter bloomFilter = 1;

}

Bloom filter internally uses two different hash functions to map a key to a position in the bit set. For tinyint, smallint, int, bigint, float and double types, Thomas Wang’s 64-bit integer hash function is used. Doubles are converted to IEEE-754 64 bit representation (using Java’s Double.doubleToLongBits(double)). Floats are as converted to double (using Java’s float to double cast). All these primitive types are cast to long base type before being passed on to the hash function. For strings and binary types, Murmur3 64 bit hash algorithm is used. The 64 bit variant of Murmur3 considers only the most significant 8 bytes of Murmur3 128-bit algorithm. The 64 bit hashcode generated from the above algorithms is used as a base to derive ‘k’ different hash functions. We use the idea mentioned in the paper “Less Hashing, Same Performance: Building a Better Bloom Filter” by Kirsch et. al. to quickly compute the k hashcodes.

The algorithm for computing k hashcodes and setting the bit position in a bloom filter is as follows:

- Get 64 bit base hash code from Murmur3 or Thomas Wang’s hash algorithm.

- Split the above hashcode into two 32-bit hashcodes (say hash1 and hash2).

- k’th hashcode is obtained by (where k > 0):

- combinedHash = hash1 + (k * hash2)

- If combinedHash is negative flip all the bits:

- combinedHash = ~combinedHash

- Bit set position is obtained by performing modulo with m:

- position = combinedHash % m

- Set the position in bit set. The LSB 6 bits identifies the long index

within bitset and bit position within the long uses little endian order.

- bitset[position »> 6] |= (1L « position);

Bloom filter streams are interlaced with row group indexes. This placement makes it convenient to read the bloom filter stream and row index stream together in single read operation.